Curator’s Message

In 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited the National Historic Site Gur Sikh Temple where this exhibit you see before you told the story of the South Asian Canadian right to the vote. The Prime Minister read the introduction and asked:

“Did the Government of the day take away the right to vote from South Asians in 1908?"

I replied,

"Yes, they did”.

He further commented,

“I am sorry to hear that. It is even more egregious to take away the right to vote by the Government when it was a right given to immigrants when they first arrived.”

These words have stayed with us for a long time because the important franchise given to our ancestors was something they fought for – for 40 long years from 1907 until 1947. Being disenfranchised left them feeling incomplete – their sense of belonging and contributing were all taken away through the legislated racism of the time.

This exhibit is part of the legacy of South Asian Canadian history through a rich and robust record of the past and highlights the many injustices faced by new immigrants to Canada. The perseverance and resilience of the early settlers to BC included lobbying, advocacy, public motivation, petitions, meetings in Ottawa and London and so much more. These stories and battles in the fight for the right to the franchise have been captured in this exhibit.

We hope you will learn from the exhibit and discover history that has not been given its due place in history.

We would love to hear from you if you have a story or insight to share about the right to vote - from the past or from today - contact us at sasi@ufv.ca.

Dr. Satwinder Kaur BainsDirector, South Asian Studies Institute, University of the Fraser Valley

Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra

Coordinator South Asian Studies Institute, University of the Fraser Valley

(DIS)Enfranchisement: 1907-1947 The Forty-Year Struggle for The Vote

This exhibit is part of a larger, nation-wide conversation commemorating 150 years of Canada’s confederation. The insertion and interjection of the South Asian Canadian experience in Canada is purposeful and meaningful in an attempt to un-silence the stories of those who were often considered the ‘other’ and who remained in the margins of Canadian historical discourse. In the early 1900’s Indian immigrants coming to British Columbia shores faced much racial, gender and cultural discrimination.

The story of The Vote is a perfect example of a narrative that is a part of the larger story of Canadian Confederation. We recognize that The Vote was much more than the act of electing Provincial and Federal leaders; it was an act of Citizenship and rights, an active participation in a process that was meant to include a selected few in the narrative of Canadian nationhood. For many others, this right was denied based on designed discriminatory and racist practice and legislation. This exhibit aims to shed light on the struggles and triumphs of South Asians’ struggle to regain The Vote, and as a narrative that is as much a part of Canadian history as any other story.

We gratefully acknowledge financial support by the Government of Canada.

Nous reconnaissons l'appui financier du gouvernement du Canada.

This exhibit was curated by the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies (now the South Asian Studies Institute) at the University of the Fraser Valley with support from the Khalsa Diwan Society, Abbotsford.

IN SOLIDARITY

We acknowledge that the National Historic Site and Gur Sikh Temple and Sikh Heritage Museum is located on the land of the unceded Sto:lo First Nations territory.

The Sikh Heritage Museum would like to demonstrate its solidarity with the Stó:lō people. We do this by acknowledging the Stó:lō peoples ongoing struggle for self-government and recognition on lands which has been theirs from time immemorial.

We recognize that the story of struggle for South Asians’ franchise and citizenship is a stark departure from the narrative and story of the Indigenous peoples on whose traditional territory this nation was built. In response, we humbly move forward as partners in this complicated history.

ENFRANCHISE: [en-fran-chahyz], verb (used with object), enfranchised, enfranchising.- legal process for terminating a person's First Nations status and conferring full Canadian citizenship. Enfranchisement was a key feature of the Canadian Federal Government's assimilation policies regarding Aboriginal peoples.

FRANCHISE: [fran-chahyz], verb- to grant a franchise to; admit to citizenship, especially to the right of voting

- to endow (a city, constituency, etc.) with municipal or parliamentary rights

DISENFRANCHISE: [disənˈfran(t)SHīz/], verb- to deprive (a person) of the right to vote or other rights of citizenship

- to deprive (a place) of the right to send representatives to an elected body

- to deprive (a business concern, etc.) of some privilege or right

- to deprive (a person, place, etc.) of any franchise or right

South Asian Canadians Today

South Asians are integral and vibrant contributors to Canadian society, heritage, culture and history. They hold prominent positions across the professional sector and are leaders in industry, government and contribute to the fabric of communities across Canada.

However, this has not always been so. The many nuanced and diverse qualities of South Asians has not always been appreciated with limited and they were not provided opportunities to contribute to Canadian society, one key feature of which was being deprived of the right to vote.

This exhibit is the story of struggle, success and contribution of South Asians in their desire to be valued as contributors to Canadian society.

Setting Sail for New Opportunities (Who were the early South Asian Arrivals to Canada?)

Story of Bishan Singh

Hello and sat sri akal (truth is the ultimate God). Let me tell you a little bit about my experience of coming to Canada. I was born in 1890 in Dhudikey, a small rural village in Punjab where I had lived all my life, attending school and after finishing grade eight, helping my father and brother on our family farm.

In 1907 my chachaji wrote from Vancouver asking my father to send me there to work and help with the family income. My father agreed and sold a section of our land for Rs. 800, buying a ticket for Rs. 14 to travel by ship from Calcutta on April 15, 1907. I boarded a steam ship run by the Jardin Company in Calcutta with about 120 other men from Punjab and travelled to Hong Kong for 18 days, paying about Rs. 44 for that leg of the journey. After waiting for many months at the Hong Kong Gurdwara with many other men, I then purchased a ticket for $65 on a steam ship run by the Canadian Pacific Company - the Empress of Japan to Vancouver. The journey was not easy as I was scared to be travelling across the seas. I didn’t know what awaited me on my arrival, although I was excited and eager to see my chacha ji.

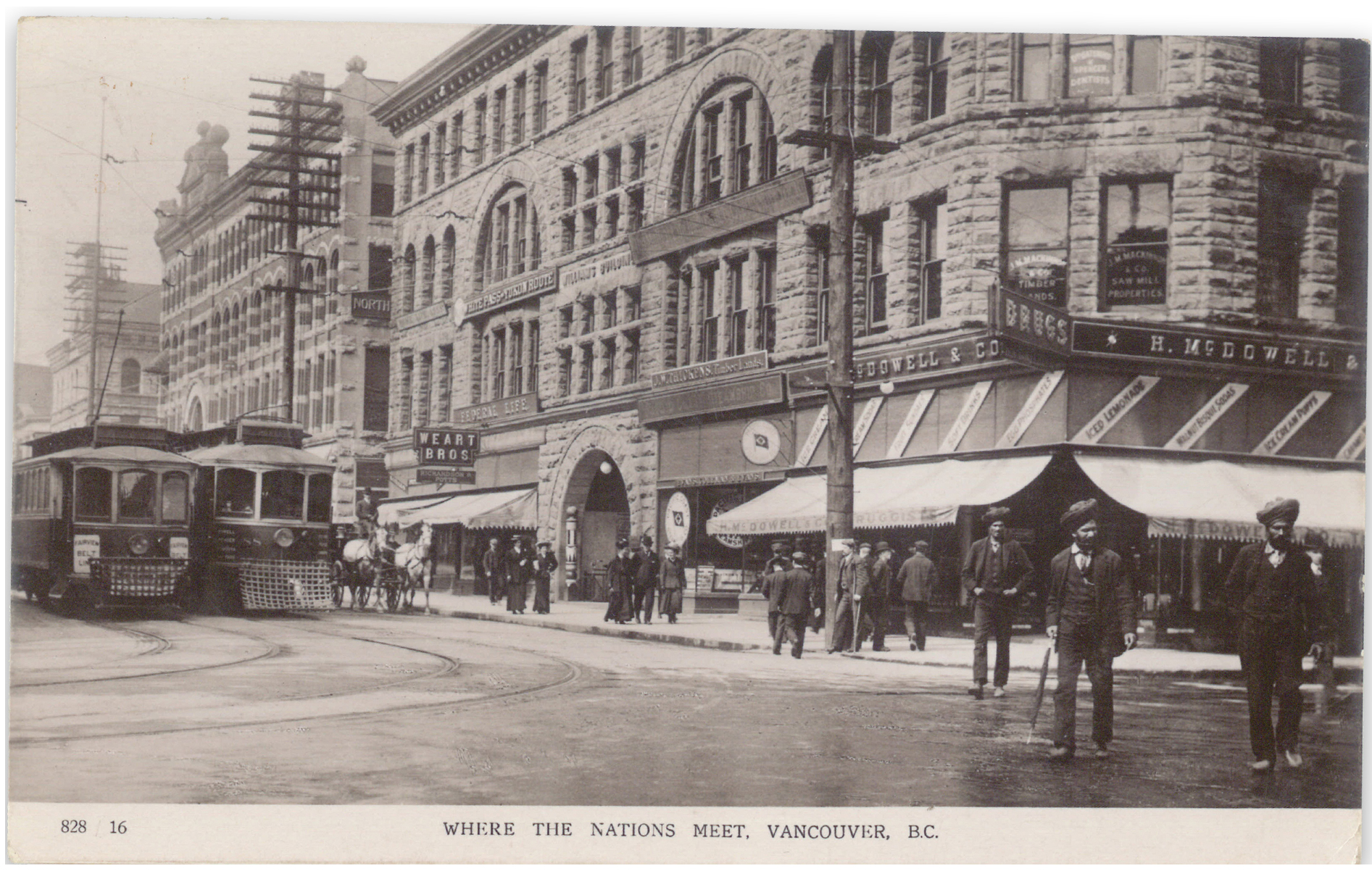

We arrived on August 26, 1907, at the Port of Vancouver in the middle of the day. My chacha ji took me to the Khalsa Diwan Society, Vancouver Gurdwara located at West 2nd Avenue to give thanks to the Almighty for having made the journey. The gurdwara provided me with meals and a place to sleep for a few days. My chacha ji took me to Fraser Mills located in New Westminster so I could start working and earning some money to pay for my boarding and lodging and to send money back to my family back home. My chacha ji also informed me about the European ways as he had some knowledge about British and European ways from his service in the British Indian army.

I soon came to understand that segregated living in Vancouver was quite normal. Before my arrival in March 27, 1907 the BC Premier William Bowser had disenfranchised all natives of India not of Anglo-Saxon parents. Only a few weeks after my arrival, on Sept 7, I also witnessed the most serious race riot by the Anti-Asiatic League in the streets of Vancouver. These moments have stayed with me as I grew old and have impacted who I am in a big way.

As you read my experiences in British Columbia, I hope you can gain an understanding of the experiences of those like me who were also disenfranchised and disempowered.

The Early Years: 1902 – 1907

At the turn of the 20th century, the Northwest area of Punjab was in a unique position in the trajectory of colonial rule under the British Empire. Having annexed Punjab in 1849 soon after the internal upheaval following the death of its Sikh ruler, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the British Empire seized on the opportunity to incorporate Sikh soldiers into their army.

Further, because many Sikh soldiers played a pivotal role in allying with the British and quelling rebellion in the First War of Indian Independence in 1857, the British rewarded many Sikhs in the military ranks.

"I came to Canada because of my chacha ji (my father’s younger brother) Partap Singh who had immigrated to Canada in 1902 from Shanghai. In 1900, my chacha ji had gone to China as part of the 3000 strong Sikh Regiment force sent by the British to China to quell the Boxer Rebellion. After the siege was lifted, he was deployed as a law enforcement officer in Shanghai by the British Army. After hearing about Canada from fellow soldiers, in 1906 my chacha ji left his service and boarded the Monteagle from Shanghai to Yokohama and arrived in Victoria on May 26, 1906. Upon his arrival, he sent a letter inviting me to come join him in Canada in January 1907. My family has a long history of service of which I am very proud of. Not only did my chacha ji serve, but my grandfather also had served in the First War of Indian Independence in 1857. He even received the Indian Mutiny Medal of 1858 from the British for his service." - Bishan Singh

South Asian men who arrived in Canada were physically sturdy and culturally an enterprising group of individuals, striking away from their homeland in search of opportunity and decent wages to support themselves and their families back home. When they arrived on British Columbia’s West coast in the early years between 1903 and 1906, for the most part they found their new home welcoming and inclusive of the rights afforded to them as British subjects in Canada. Until 1906 South Asian immigrants received almost no government or press notice and there were no immigration laws or regulations that impeded or affected their entry to Canada in these first years. However, many of the initial freedoms they enjoyed would soon be revoked.

From 1904 to the 1940s, 95% of all South Asian immigrants to Canada were Sikhs from the Punjab region of India. Sikhs in particular have traditionally been extremely resourceful, independent and undaunted by the idea of taking risks to better their situation. This character, along with previous British army experience made international migration to British Canada a natural movement. An agrarian background and farming tradition in the Punjab also lent itself to adaptation of the Pacific Northwest working environment.

The first Sikh Punjabi immigrants to Canada arrived in the summer of 1903, when five Sikh men landed in Victoria and another five Sikh men landed in Vancouver. Altogether about thirty men came to Canada between 1903 and 1904.

| South Asian Immigration to Canada, 1904 - 1907 | |

|---|---|

| 1904-05 | 45 |

| 1905-06 | 387 |

| 1906-07 | 2124 |

| 1907-08 | 2623 |

| Total | 5179 |

Buchignani, N., Indra, D. M., & Srivastiva, R. (1985). Continuous journey: A social history of South Asians in Canada. McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

Work Life

"When I started working in the Fraser Mills in 1907, I was earning 35 cents an hour, working twelve hours a day, six days a week with Sundays off. I found lodging in shared accommodations in New Westminster with 12 other Sikh men who all shared space, chores and responsibilities. I learned to do things I had never done before, such as cooking, laundry and cleaning the house. Throughout this time, I missed my parents and brother, sister and nephew dearly, and I would await letters from my family telling me about how things were at home. I saved my money diligently and sent all my savings to my father so that he could buy more land and look after the family. My needs have been few and I have lived frugally in a bachelor society made up of men like me, some young and some old." - Bishan Singh

Almost all the men who arrived in British Columbia worked in labour industries including forestry, fishing and railway. Since the Canadian government was preoccupied with restricting Chinese and Japanese immigration at the time, South Asians were quite easily able to find employment. On average, these men earned from $1 to $1.25 a day, but this was less than the pay received by workers of European descent. Some socially conscious employers however, did pay their South Asian workers up to $1.50 to $2.00 a day.

Since wages were so low South Asian men lived together - often between twenty to fifty men living under the same roof in homes that were commonly referred to as bunkhouses. Often, in an effort to find forestry related work, many men would travel from cities across BC including: Abbotsford, Golden, Paldi, Youbou, Honeymoon bay, New Westminster, the Cowichan Valley, Prince George, Terrace etc.

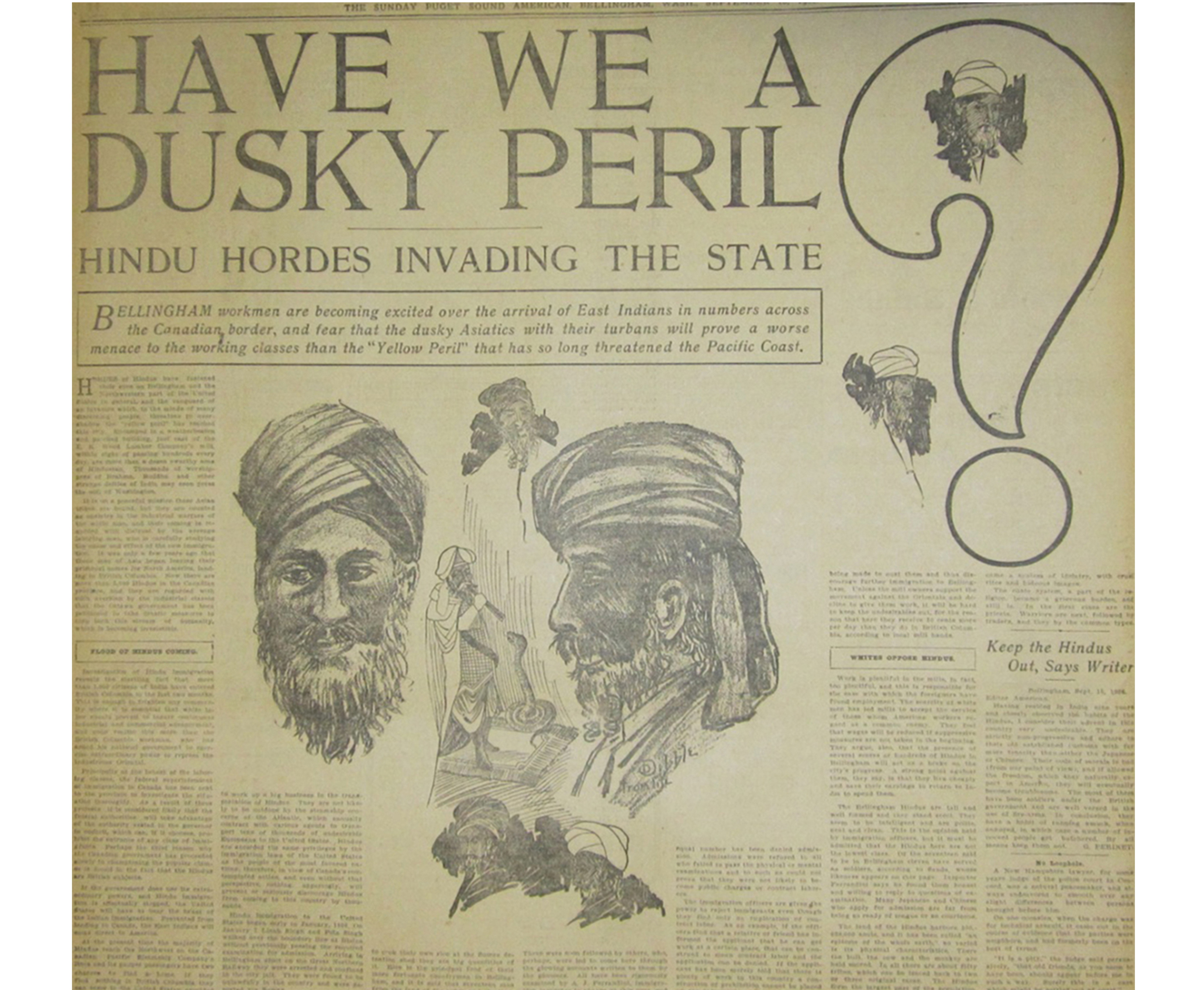

Along the years as Indian migration into British Columbia increased, so did overt racial tensions which had for the early years remained nominal. In 1906 after some 700 South Asians had arrived, the Canadian government suddenly started to take notice. Furthermore, because some employers preferred to hire Punjabis due to their work ethic at lower pay, many Europeans resented their presence in Canada. A great deal of racial tension and strife ensued from 1906 onwards as South Asians were laid off from work, were barred from entering public facilities, evicted from their homes, physically abused by the police, individuals, and by the local press and media. The formation of racist and exclusionary groups such as the Asiatic Exclusion League produced discrimination and mistreatment of the South Asian, Chinese and Japanese communities. The 1907 riots led by The League is demonstrative of the challenges these immigrant communities faced as their homes, businesses, and livelihoods in general were meaninglessly destroyed.

1907 – The Era of Disenfranchisement

To hinder South Asian migration to Canada, the government implemented the infamous “continuous journey” regulation on January 8, 1908, which decreed that migrants had to arrive in a continuous journey at a Canadian port from his or her country of origin.

Another significant regulation demanded that all incoming migrants from Asia must have in their possession a sum of $200.00, which was an inconceivably large amount of money. In comparison, European migrants were only required to have $20.00 in their possession.

Troubles in Canada were further exasperated by the lack of family units for men from Asia. Canadian regulations at the time restricted Punjabi women and children under the age of eighteen from entering Canada, and such was the case that from the 1904 and 1920, only nine Punjabi women migrated to British Columbia. The majority of men were left alone, without their wives and families and lived amongst themselves in compact lodgings.

In March 1907, British Columbia Premier William Bowser introduced a bill to disenfranchise all natives of India not of Anglo-Saxon parents. In April 1907 South Asians were denied the vote in Vancouver by changes to the Municipality Incorporation Act. The federal vote was denied by default as one had to be on the provincial voter’s list to vote federally. South Asians would be barred from the political process in Canada for the next 40 years until 1947 when the vote was finally reinstated after much struggle.

1907 – Disenfranchisement: The impact

Many in the South Asian community protested the discriminatory treatment they faced. For example, in November 1909, Teja Singh and Hari Singh presented their case on the restrictions of South Asian migration while in England. Others, such as Guru Dutt Kumar, tried to forge a unified South Asian identity through the newspaper, “Swadesh Sevak,” which was eventually censored. Bhag Singh, the President of the Khalsa Diwan Society, Vancouver, went to India to pressure the British government to take action. Even the average South Asian community member took to the streets in order to publicly protest their untenable conditions and by sending petitions to the Canadian, British and Indian governments.

To get the immigration ban on Punjabi women and children lifted, the Khalsa Diwan Society, Vancouver and many of its management and community members worked tirelessly to send delegations to Ottawa, sought support from the British Empire, and pursued legal help from local Vancouver lawyers. But these pleas would usually fall on deaf ears and any changes were laboriously slow. The emotional and relationship loss between a husband and wife cannot be underestimated. The Canadian Government’s methods to hinder immigration was effective as the Immigration Act that was overhauled including the Continuous Journey regulation. The amended Act now gave sweeping powers to the government to exclude people explicitly on the basis of race.

On July 30th 1918, the Canadian Government received word from the British Ministry of Information that, “Indians already permanently domiciled in other British countries would be allowed to bring in their wives and minor children” (Abbotsford Post, 1918). However, the first wives would not arrive until 1921 and in that year the first Indo-Canadian child was born.

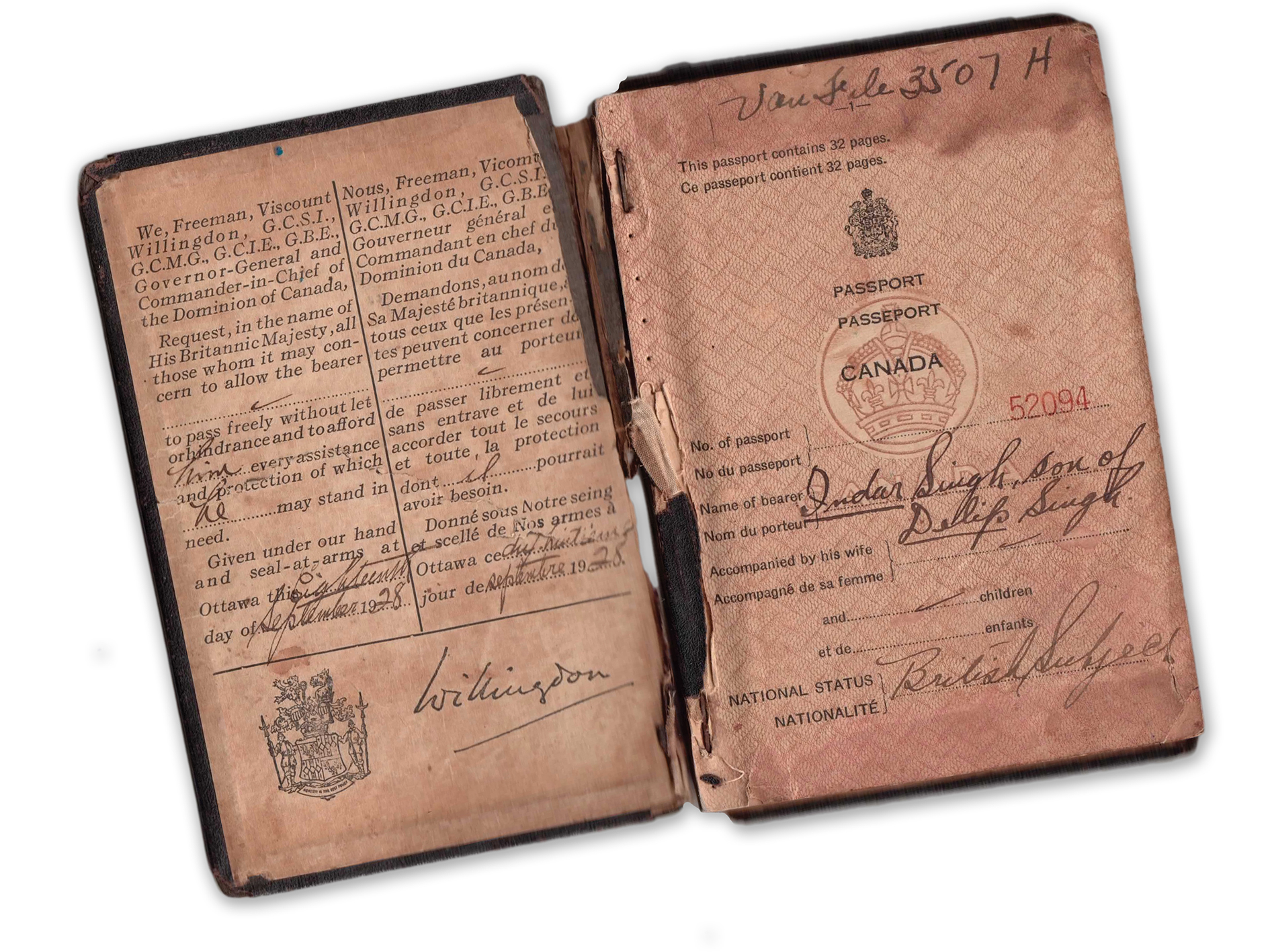

- Letters from Kartar Kaur Gill in India to her husband Indar Singh Gill in Abbotsford, July 14, 1937: You can understand how my soul has become lonesome without you. I hope, my Sardarji that you would not worry. By God’s grace we shall meet again. We must have committed a grave sin that we are still apart, my Sardarji if I had known, I would have never let you go.

- Letter from Kartar Kaur Gill in India to her husband Indar Singh Gill in Abbotsford estimated in 1942: What should I write about you returning home, I don’t understand anything, you always leave me with false hope. Twelve days are toilsome enough and it has been twelve years now.

- Letter from Kartar Kaur Gill in India to her husband Indar Singh Gill in Abbotsford, 1946: The ladies sing songs taunting me about bearing this 20 yearlong separation. I write this in agony as what do I live for, I have not seen you in years. You gave me the hope that you will come back in five years, those five years are long gone. We are alive yet separated. If it is in God’s wish he will unite us, else it is what it is. I need you in my life, I don’t need anything else.

Its been one year since I have been in British Columbia, Canada and I am feeling so much pain. I feel so lonely, hurt and sad. I am not allowed to go in certain restaurants or even eat at restaurants. The people that I rent their basement from wont allow me to cook my own food. They refuse to let me eat. I am lost with where to go and where I can eat. The gurdwara has become my sanctuary for which I am grateful. But the pain does not subside. I am pushed and shoved aside by Europeans. I am told to go back home Hindoo." - Bishan Singh